The Smackdown

British actress Tilda Swinton is best known here for her Oscar-winning supporting turn as an icy, villainous lawyer in Michael Clayton (2007), but neither the role nor the performance really demonstrates what this woman is capable of. Again and again, she’s shown a willingness to take on roles that would terrify most actresses, be it due to the subject matter, the character’s off-putting actions, or what the part physically demands (she is apparently comfortable with all manner of nudity and sex scenes; ever see Young Adam?), and it is this complete lack of fear or modesty combined with her striking physical features (alabaster skin, bright red hair, really damn tall) and just plain uniqueness that have made her such a darling of the independent film world.

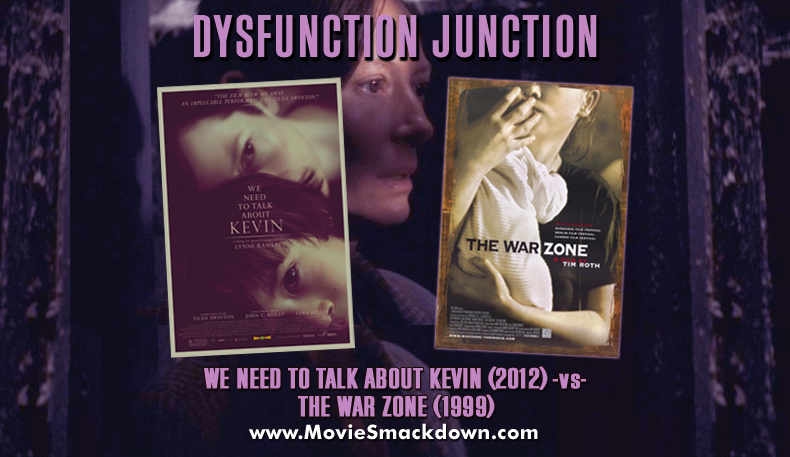

Basically, she’s up for pretty much anything, and as a result, her name in the cast is usually a harbinger of edgy, challenging and controversial material (keeping in mind that she’s also the White Witch in those godawful Narnia movies; hey, a girl’s gotta make a living). If it’s a domestic drama about parenting teenagers, there’s also a good chance that it will be hella depressing… bringing us to this week’s Smackdown, which couldn’t be much less date-movie-friendly, as we pit bleak incest drama The War Zone (1999) against the newly released and equally bleak psycho-child drama We Need to Talk About Kevin.

That said… let the best movie Swin’! (Sorry.)

The Challenger

The Challenger

In We Need to Talk About Kevin, Swinton plays Eva, currently a lonesome pariah in her Connecticut community for reasons we gradually piece together through the flashbacks she relives while at her miserable filing job and while scraping away the red splotches of paint that vandals throw at her run-down house. We follow her downward spiral from the hedonistic liberation of cavorting at a tomato-throwing festival in Spain to settling down with a sweet lug (fellow indie stalwart John C. Reilly), reluctantly becoming pregnant by him, and giving birth to Kevin, who is played at advancing ages by the eerily well-matched Rock Duer, Jasper Newell, and Ezra Miller.

Kevin is a problem child from day one. As a baby, his crying is so incessant that Eva seeks out the noise of a jackhammer for solace. As a toddler, he is sulky, creepily uncommunicative and defiant of his mother in every way possible, including toilet training. And as a brooding, snide and just plain evil teenage, he gleefully articulates his hatred of her at every opportunity, menaces his younger sister and focuses on his archery skills, leading to the tragedy that destroys their lives.

The Defending Champion

The Defending Champion

The War Zone opens with a family of four getting in a bad car accident in the rain on the way to the hospital while the mother (Swinton) is in labor. That they all survive intact, including the baby, makes this by far the most cheerful sequence of the movie.

We soon learn, along with mopey, acne-scarred teenager Tom (Freddie Cunliffe), that his sultry older sister Jessie (Lara Belmont) has been the passively consenting victim of the worst kind of sexual abuse at the hands of Dad (Ray Winstone). Timid and naive Tom is at a loss for how to react. When he angrily confronts Jessie about it, she denies it; after he discreetly videotapes one of their trysts in a stone bunker (an almost unwatchably wrenching scene), he quickly destroys it, perhaps deeming it too monstrous to show anyone.

Jessie is clearly opposed to the situation but insists on keeping it secret, leaving Tom caught between his loyalty to his sister and his outrage (perhaps mixed with jealousy, depending on your reading) at the pain being inflicted on her.

The Scorecard

Is Kevin’s psychotic brattiness the cause of Eva’s misery, or is Eva’s misery the reason Kevin is a psychotic brat? Kevin provides no easy answers, but it’s a riveting exploration of the question. The parents I’ve discussed it with seem to sympathize largely with Eva (one shrugged, “She just got a bad one.â€), and for much of the time, it’s hard not to. Whatever her parental failings, she clearly doesn’t deserve the heartless scorn of her community: Her home and car are vandalized, her co-workers ignore and shun her, and one grieving parent sucker-punches her as she walks past. Nor does Kevin’s relentlessly nasty attitude toward her seem anywhere near warranted, even after she remarks to him as an infant, “Before you were born, Mommy used to be happy. Now Mommy wakes up every day and wishes she were in France!â€

Eva is the dictionary definition of “unreliable narrator,†so we can’t help but wonder how accurate her subjective memories are and what she’s choosing not to remember. But Swinton, in another brave and fascinating performance, gains our sympathy, if not entirely our trust. She is well-matched by all three “Kevins,†particularly Ezra Miller, an indie star on the rise, who played a similarly misanthropic teen in the far tamer Another Happy Day and has clearly already mastered the art of being detestable. Still, it is Swinton’s heartbreaking work that haunts us long after the credits roll.

Kevin was directed and co-adapted (with Roy Kinnear from a popular epistolary novel by Lionel Shriver) by Lynne Ramsay, a Scottish filmmaker and former cinematographer who became a critical darling with her first feature, the excellent coming-of-age story Ratcatcher (1999). After a second, less successful film (Morvern Callar), she is back and at the top of her form here, expertly guiding us through the jagged, complicated chronology and giving this potentially static story a distinctive look and a soundtrack peppered with oddly cheerful oldies like Buddy Holly’s “Every Day.†From the arresting opening shot of a sea of bodies writhing around in a vat of tomato sauce, you won’t be able to look away from this film, and particularly not from Swinton.

The War Zone is a far more straightforward film, but no less enigmatic. Obviously, Dad is the monster here, one made all the scarier by the great Ray Winstone, playing him likable and seemingly caring much of the time, but barely hiding the sickness and hair-trigger temper beneath. Far more puzzling ambiguities lie in the relationship between Jessie and Tom, who seem oddly comfortable in various states of undress with each other, cuddling in bed together and sharing personal details. Why does Tom hesitate so long before doing anything about what he’s learned? Is he gathering evidence with the intent of exposing the crime, or is he titillated by it? Or is he simply curious about the previously foreign world of sex? The movie (adapted by Alexander Stuart from his own celebrated novel) leaves a lot to the viewer’s imagination, particularly an unsettling ending that is open to multiple interpretations, which elevates it above the movie-of-the-week material it could easily have been.

The film thus far represents the sole directing credit of Tim Roth, one of the great actors of his generation. He gives it the washed-out, kitchen-sink realism look of Mike Leigh (one of his early directors), and like Leigh’s his direction is sensitive and unobtrusive. He also cast the four leads beautifully, with veterans Winstone and Swinton meshing perfectly with newcomers Cunliffe and especially the luscious Belmont, who deftly handles some difficult and truly excruciating scenes that far more seasoned actresses would have balked at. Indeed, some of The War Zone is almost too difficult to watch, but for those who can stomach it, it’s a shattering experience that has lost none of its potency over the years.

The Decision

Oh, it’s so refreshing to do a Smackdown between two such intelligent, daring, uncompromising films. Both take on risky, taboo subject matter in ways that haven’t been done before, refusing to simplify or compromise their messages, and both leave plenty open for debate. For Swinton fans, the obvious choice is her star turn in Kevin over her rather limited role in War Zone. But damnit, both films are so deserving of larger audiences than they’ll ever get, it’s a shame to have to pick one. If you haven’t seen War Zone, it’s fortunately available on Netflix Streaming, and due to its realistic, unadorned style, doesn’t lose its impact on the small screen, whereas the beautifully photographed Kevin really should be seen in a theater.

Both films are serious downers, but they are master classes in writing, directing and acting. I’m going with Kevin, mainly because it’s just now hitting the theaters and thus could use the attention more, and to counter the fact that some critics (and Rex Reed) just plain didn’t get it. Go see it, and I recommend reserving some time afterward for discussing it. You’re going to need to talk about We Need to Talk About Kevin.

Leave a Reply